Sometimes the bravest leadership move isn’t pushing harder—it’s stopping.

No can-do innovator ever wants to acknowledge this, but there are plenty of times that no matter how much grit, creativity, and sheer willpower you pour into a project, it just won’t get off the ground.

I’ve been there more than once—watching a well-intentioned initiative sputter despite repeated pushes, creative workarounds, and every ounce of effort my team could muster. We just could not get our leadership to sign off on a controlled experiment where we wanted to offer a menu of incentives to a cohort of junior officers to see which things they would take and which they passed on in exchange for additional service obligations. Not because of the incentives—but because we had a group that would get the incentives, and a control group that would not get them.

“That’s not fair!” they said. “You will create haves and have nots!” they said. And no matter how many times we explained that not everyone could get a crack at the menu of incentives because it was an experiment, our culture could not accept that we did not offer everyone the same opportunity (our view of fairness as sameness is a recurring issue; I’ve written about it previously).

This became an insurmountable obstacle, and we had to set the project aside to pursue other experiments.

In the Army, our instinct is to find a way to get it done. We pride ourselves on being the people who overcome impossible odds. But there’s a point where pushing harder stops being perseverance and starts being waste—of time, energy, resources, and goodwill. In air assault operations, when a load becomes tangled or unmanageable mid-flight, we “cut slingload” to protect the aircraft and crew. In change work, sometimes you have to cut slingload the same way.

This week’s, we’re going to talk about recognizing those moments. How to tell the difference between temporary resistance and terminal opposition. How to decide whether to pause, pivot, or pull the plug. And—most importantly—how to exit gracefully, protecting both relationships and trust so that when the next opportunity comes, you’re ready to lift again.

Let’s decode it. 🚀

Knowing When to Let Go of a Change Effort

Sometimes, no matter how much grit, creativity, and sheer willpower you pour into a project, it just won’t get off the ground. Our instinct is to get it done, but we often end up with a proverbial frustrated load where we need to cut slingload.

The challenge is knowing when to hold it and when to release the load. It’s about knowing that this isn’t giving up—it’s about making smart strategic calls so you can fight the right battles, cut your losses when you need to, and fight another day.

Most leaders—and especially high performers—are wired to finish the mission. That’s a strength in the right context. But in change initiatives, that mindset can turn into a trap. Why, if we’re smart high performers, do we do this?

We keep pushing because:

Sunk cost bias – We’ve already invested too much time, money, and political capital to walk away—or at lest too much to explain to our stakeholders that we really needed to walk away.

Fear of perception – We worry that stopping will look like failure, weakness, or incompetence. No one wants failure or the word “can’t” tied to their records, even if the problem is literally impossible.

Overconfidence – We believe we can solve any problem with enough effort (even if a lot of other really smart capable people have tried to solve it before, we haven’t yet, so this time will be different).

Attachment – We’ve become emotionally tied to the idea or the vision. It’s become a favorite pet project, something we want to shepherd to success.

These are human impulses. But if you’re leading change, you can’t afford to let them cloud your judgment.

Signs You May Need to Cut Slingload

Here are a few red flags I’ve seen—and sometimes ignored—that signaled it was time to pause or walk away:

Persistent, immovable resistance – You’ve built the coalition, told the story, shown the data…and the same key stakeholders remain firmly opposed. You can’t move them or remove them, so you’re stuck.

Misaligned incentives – The change runs counter to how people are rewarded or recognized, and leadership won’t adjust the systems to reward new behavior.

Shifting strategic priorities – Your project is no longer in line with the organization’s top goals, which translates directly to prioritization for resources, people, and support.

Resource starvation – Promised funding, staffing, or access never materializes, despite repeated assurances—usually indicates sign #3 but a more passive aggressive version.

Erosion of trust – The initiative is creating friction or damaging critical relationships.

These signs don’t always mean you have to end the project—but they do mean it’s time for a deliberate reassessment.

Temporary Resistance or Terminal Opposition?

Before cutting slingload, you have to diagnose the nature of the pushback:

Temporary Resistance – Usually driven by uncertainty, overload, or the “not invented here” syndrome. These can often be addressed with better communication, small wins, and visible leadership support.

Terminal Opposition – Rooted in deep structural misalignment, entrenched political battles, or leadership turnover that removes your champions. These won’t shift without major environmental changes.

The distinction matters because temporary resistance calls for persistence and adaptation. Terminal opposition calls for a pivot—or an exit.

Pause, Pivot, or Pull the Plug

When you’ve hit the point of reassessment, you have three main options:

1. Pause

Sometimes the smartest move is to stop pushing temporarily. This might be the case when:

A key leader is transitioning in or out.

The organization is in crisis mode and can’t focus on your change.

You need to regroup and rebuild support.

A pause preserves relationships and keeps the door open for the right timing later.

2. Pivot

If the core idea is solid but the packaging or pathway isn’t working, pivot.

Align it with a higher-priority initiative.

Narrow the scope to a smaller pilot.

Shift ownership to a different team or function that has more credibility or resources.

Pivots can reframe the effort in a way that makes it more palatable—and more likely to succeed.

3. Pull the Plug

When the costs outweigh the benefits, or the political environment is actively hostile, it’s time to release the load.

Make the decision swiftly and communicate it clearly.

Avoid blaming individuals—frame it as a strategic choice based on the current environment.

Capture lessons learned so future efforts don’t fall into the same traps.

Pulling the plug is not failure—it’s resource management.

Exiting Gracefully

How you end a change effort matters almost as much as how you start it. A messy exit can damage your credibility and poison the well for future initiatives.

When stepping away:

Be transparent – Share the “why” in a way that focuses on the strategic decision, not personal shortcomings.

Thank contributors – Acknowledge the time, ideas, and energy invested, even if the project didn’t land.

Offer a vision forward – Even if this project ends, articulate how the underlying problem or opportunity can still be addressed in the future.

Done well, ending a project can actually strengthen trust and position you as a leader who knows when to make the hard calls.

Lessons From the Landing Zone

I’ve had to cut slingload a few times in my career—projects I believed in deeply but couldn’t get to safe altitude. At first, each one felt like a loss. Over time, I’ve realized those moments were critical for my growth as a change leader.

Cutting slingload on these projects:

Preserved political capital for initiatives that did succeed.

Freed up time and energy for higher-impact work.

Protected relationships that became critical for future change efforts.

The truth is, no one can run every mission. The leaders who make the most impact aren’t the ones who push every project to the bitter end—they’re the ones who know when to release the load so they can fight another day.

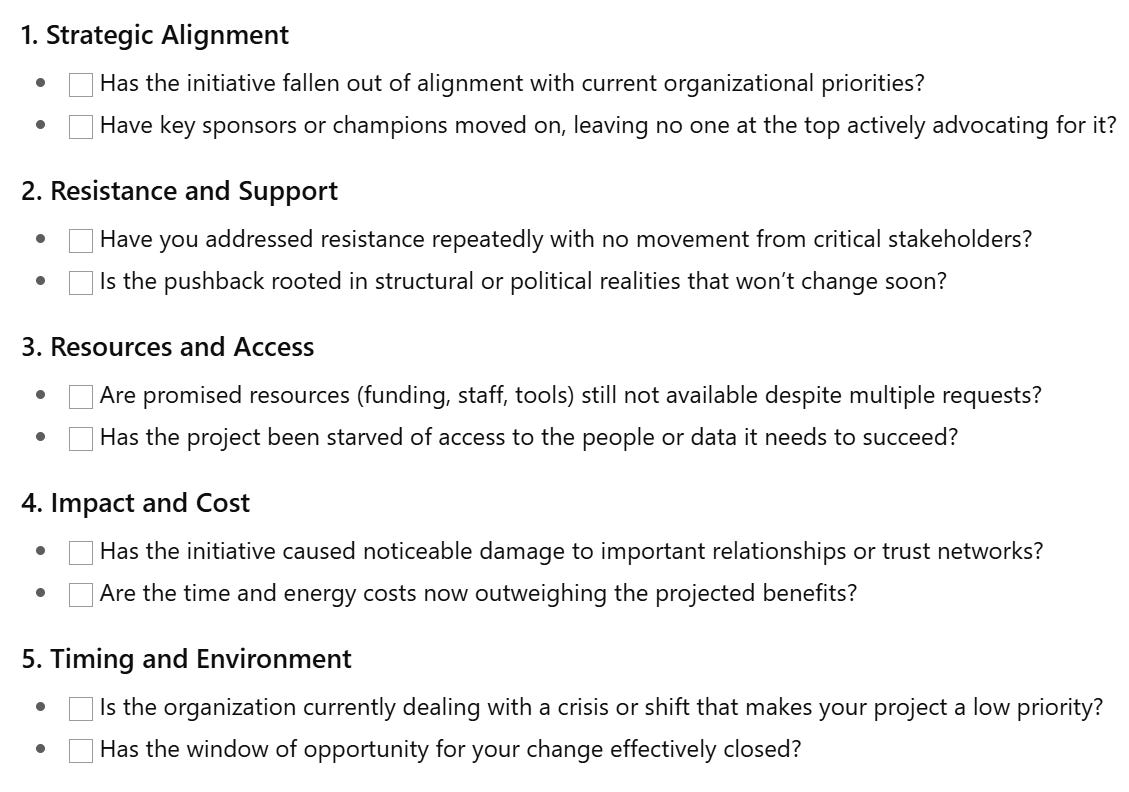

Want a checklist? I like checklists!

Is It Time to Cut Slingload?

A quick self-check for change leaders

Answer each question honestly. If you find yourself saying “yes” to most of these, it may be time to pause, pivot, or pull the plug (printable image).

Score yourself:

0–3 “Yes” answers: Stay the course, but watch for emerging issues.

4–6 “Yes” answers: Consider a pause or pivot to reframe and rebuild support.

7+ “Yes” answers: It’s likely time to cut slingload and redeploy your energy elsewhere.

The Bottom Line

Giving up on a project is never the first choice, whether it’s in a military mission or in an innovation program. It’s the last resort, taken to protect the mission and the people and the resources you need to fight another day.

If you lead change long enough, you’ll face moments where the smartest, most strategic move is to let go—so you can keep flying. Recognizing those moments isn’t weakness. It’s leadership.

Because sometimes the only way to save the mission is to release the load.